5 Common Mistakes Players Make When Reviewing Hand Histories

Hand history analysis is a critical component of skill development in strategic games such as poker. Systematic review of prior decision-making enables players to identify errors, improve exploitative adjustments, and refine theoretical understanding. However, many players approach this process inefficiently, which reduces the potential learning value. This article highlights five common mistakes observed in hand history reviews, situates them within cognitive and behavioral science, and provides evidence-based recommendations to optimize the learning process.

Hand histories represent structured records of gameplay decisions in poker and similar games of incomplete information. Reviewing these records allows players to evaluate both tactical choices (bet sizing, position, range considerations) and strategic frameworks (long-term expected value, exploitative deviations). Previous research in learning sciences emphasizes that deliberate practice—the intentional repetition and analysis of performance—is necessary for skill mastery (Ericsson, 2006). Despite this, many players engage in inefficient review behaviors that diminish the value of post-game analysis. This article systematically addresses five common mistakes in hand history review, supported by psychological and decision-making theory.

Mistake 1: Results-Oriented Thinking

A prevalent bias among players is to evaluate a hand primarily by its outcome rather than the quality of the decision process. Cognitive psychology identifies this as outcome bias (Baron & Hershey, 1988), in which individuals conflate the results with the quality of their decision. For example, a player may justify a poor call because it ultimately led to a win, or dismiss a correct fold because the board would have developed favorably.

Recommendation

Players should focus on expected value (EV) and strategic soundness rather than short-term variance. A hand review should explicitly separate process quality from outcome, emphasizing whether the decision was mathematically and strategically justified at the time it was made.

Mistake 2: Ignoring Contextual Variables

Some players isolate a single decision point without considering broader game dynamics, such as table image, stack depth, position, and opponent tendencies. This reductionist approach strips away critical information. Research on situated cognition (Greeno, 1998) demonstrates that decisions cannot be meaningfully analyzed outside of their contextual environment.

Recommendation

When reviewing a hand, players should annotate all relevant variables: effective stack sizes, table position, opponent statistics (e.g., VPIP/PFR in online settings), and tournament phase (if applicable). Comprehensive review requires situating the hand in the broader strategic ecosystem.

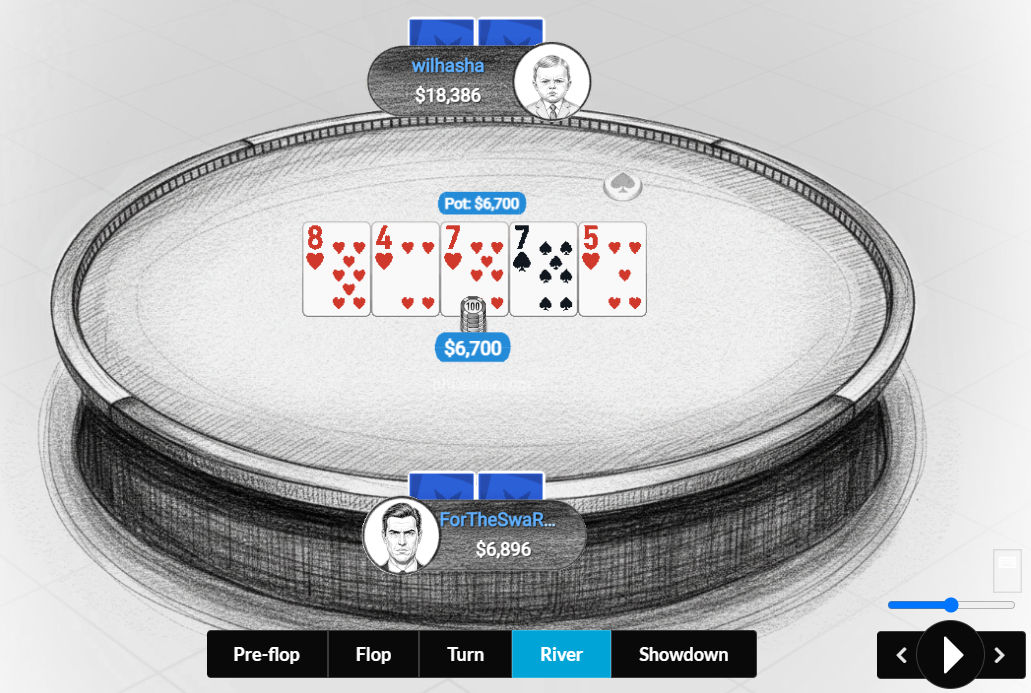

Mistake 3: Over-Reliance on Memory

Players frequently attempt to recall hands from memory rather than reviewing the raw data. Memory science indicates that human recall is subject to reconstruction errors (Schacter, 1999), leading to distortion of pot sizes, bet sizing, and even opponent actions. Such inaccuracies compromise analysis quality.

Recommendation

Players should consistently use objective hand history records exported from tracking software. Annotating directly within the software or in external databases ensures fidelity of information and reduces reliance on fallible memory.

Mistake 4: Neglecting Alternative Lines

A common pitfall is analyzing a hand through only the line actually taken (e.g., calling a flop bet) without considering realistic alternatives (e.g., raising, folding). This reduces the depth of learning by reinforcing a narrow decision pathway. Game theory and decision science highlight the importance of counterfactual reasoning—evaluating “what if” scenarios to strengthen adaptive expertise (Byrne, 2005).

Recommendation

During review, players should systematically evaluate alternative actions. For each decision point, one should ask: What would be the expected outcome if I had taken a different line? This broadens tactical awareness and prepares the player for diverse future scenarios.

Mistake 5: Lack of Structured Review Process

Many players engage in unstructured browsing of hands, reviewing them sporadically or only after emotionally charged losses. This approach lacks consistency and systematic methodology. Educational research indicates that structured review schedules and reflective practice are more effective than ad-hoc analysis (Kolb, 1984).

Recommendation

Implement a structured review protocol, such as:

- Selection criteria – Identify hands based on EV thresholds, high pot size, or uncertainty.

- Categorization – Group hands by theme (e.g., 3-bet pots, river bluffs).

- Systematic evaluation – Apply consistent frameworks (e.g., range analysis, solver comparison).

- Reflection log – Document findings to track recurring leaks and improvement over time.

Conclusion

A hand history review is an essential element in developing expertise in decision-based games. However, common errors—including results-oriented thinking, ignoring context, relying on memory, neglecting alternative lines, and lacking structure—impair learning efficiency. By applying evidence-based strategies grounded in cognitive science and deliberate practice, players can optimize review sessions, accelerate skill acquisition, and improve long-term performance.

References

- Baron, J., & Hershey, J. C. (1988). Outcome bias in decision evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(4), 569–579.

- Byrne, R. M. J. (2005). The Rational Imagination: How People Create Alternatives to Reality. MIT Press.

- Ericsson, K. A. (2006). The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance. Cambridge University Press.

- Greeno, J. G. (1998). The situativity of knowing, learning, and research. American Psychologist, 53(1), 5–26.

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Prentice-Hall.

- Schacter, D. L. (1999). The seven sins of memory: Insights from psychology and cognitive neuroscience. American Psychologist, 54(3), 182–203.